What is my research project about? Part 1

As my home page mentions, I am an earthquake geologist-in-progress. I look at subduction zones where one tectonic plate is diving underneath the other in order to figure out the mysteries of subduction earthquakes. To be more specific, I look at a particular class of earthquakes: slow earthquakes. Slow earthquakes are earthquakes that release almost the same amount of energy as a regular earthquake but unlike a regular “fast” earthquake, the energy is released over days and months. Most often, people cannot really “feel” the slow earthquakes but instruments deployed into the oceans or along coasts can identify the slow earthquakes in progress.

Slow earthquakes are exciting for several reasons. These earthquakes fit into the broader earthquake cycle and could provide us possible insights into how earthquakes originate, how does the energy transfer takes place along the subduction zone, and if these “unfelt” earthquakes can provide us a prior signal for a larger “devastatingly felt” earthquakes. To find the answer to these questions, researchers are probing this phenomenon from different realms.

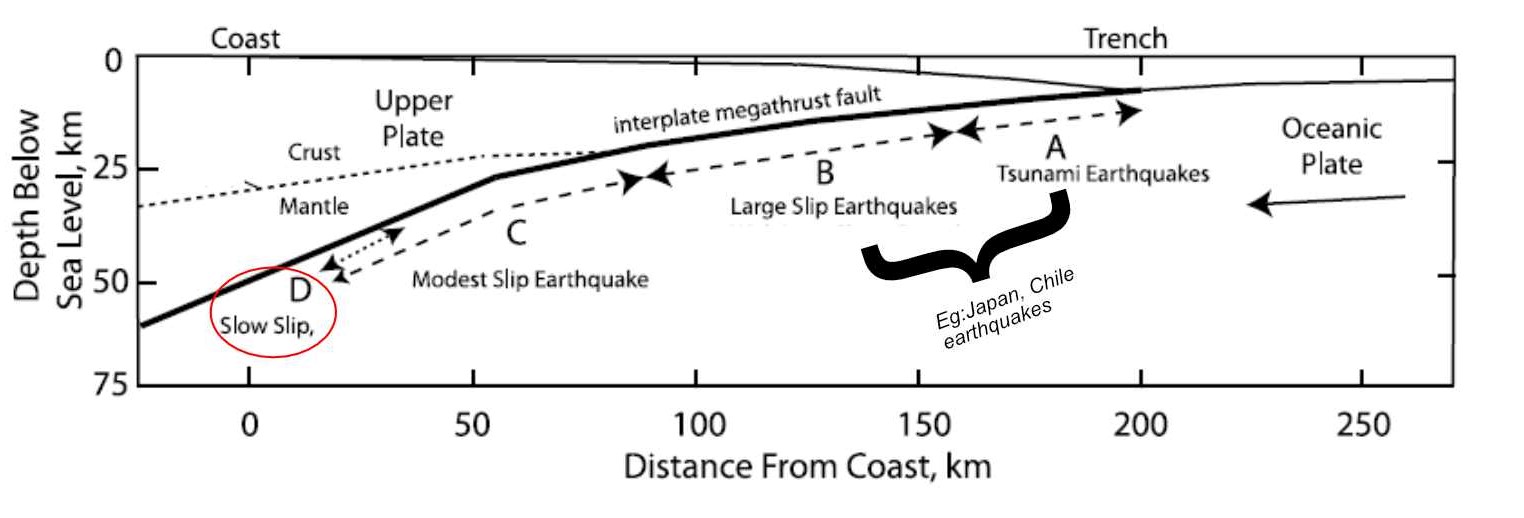

A diagram of the subduction zone showing the different kinds of earthquakes. I study Slow Slip in zone D, marked by the red circle. The large earthquakes that we hear about in the news happens in zone A and B. Modified from Lay, 2012.

A diagram of the subduction zone showing the different kinds of earthquakes. I study Slow Slip in zone D, marked by the red circle. The large earthquakes that we hear about in the news happens in zone A and B. Modified from Lay, 2012.

An earthquake geologist tries to understand the signatures of earthquakes as they are preserved in the rock record. This information gives us crucial insights into the mechanical understanding of how the earthquake originated and moved through the rocks. Since present-day earthquakes occur at depths that are not accessible to us, we look at rocks that possibly hosted ancient, fossilized earthquakes with the assumption that the way earthquakes occurred in the past are still in operation today. Usually, when fast earthquakes occur, the surrounding rock either shatters, melts, or experiences very fast chemical reactions that change the rock’s inherent properties. Geologists have devised several ways of identifying such signatures in the rock record for these fast earthquakes. However, the signatures left behind by slow earthquakes are not known. This is where my project comes in. And that is why I travel to California where an ancient subduction zone, called the Franciscan subduction zone, was once active. Based on the rock compositions, we assume that the conditions experienced by the Franciscan rocks are similar to the conditions that are currently active at the source depths (>30km) of slow earthquakes along the modern-day subduction zones. Over time, the Franciscan rocks have been brought to the surface which gives us a wonderful opportunity to explore them and find our missing clues.

In the next part, I will talk more about my field area of Angel Island and its geology.